I am a dietitian. I do not deprive; I nourish. I do not tell people what to eat; I tell people they deserve to eat. I don't tell them how many calories they need; I tell them that ALL their needs are valid. I don't tell them to limit their sugar or fat intake; I tell them that to enjoy food is to be human. I tell them that they deserve nourishment. I tell them they are not a failure for losing control; I tell them they are stronger for listening to their needs. That they do not deserve to treat themselves with food in the same awful ways that others have treated them. It pains me that I cannot convince them all that they are worthy. They cannot all see what I see....that they are precious. That their body deserves to take up space. To have stores of fat that will protect them from life's hardships. That their "problem with food" is not in the eating of food, but in feeling that they do not deserve to eat it. I wrote these words in response to the death of a dear, precious, worthy client. A beautiful soul who I will always remember, and who I will never regret trying to convince day in, and day out, that she was worthy of nourishment. Please take these words to heart and carry them with you to nourish your whole self.

4 Comments

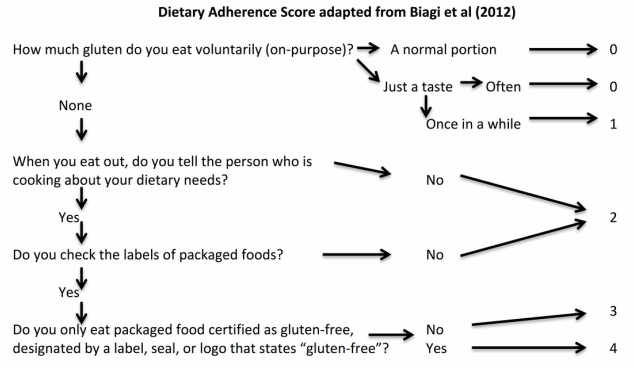

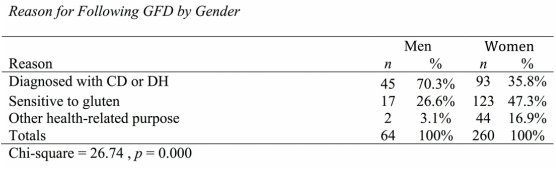

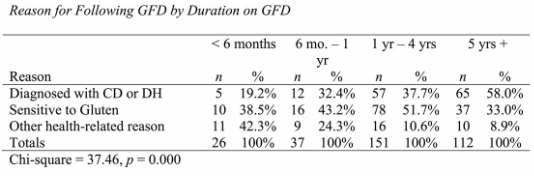

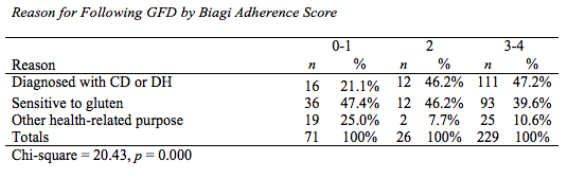

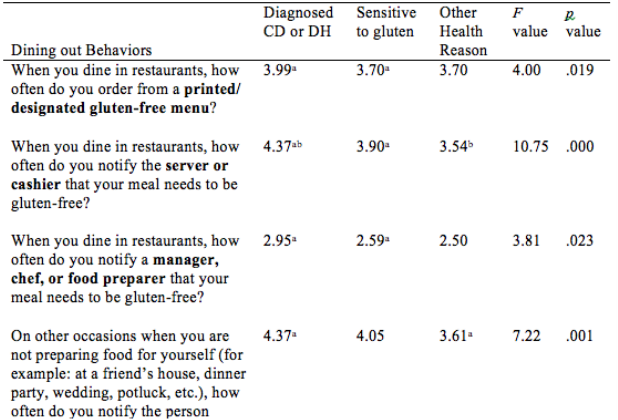

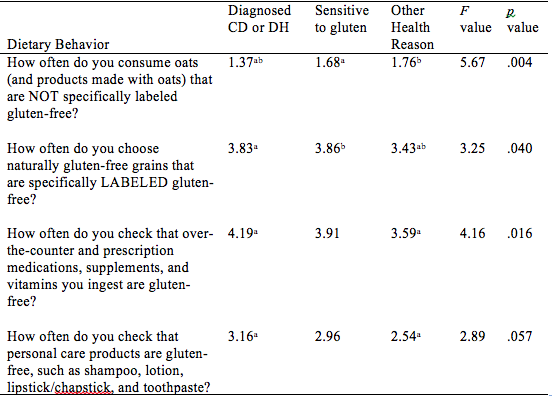

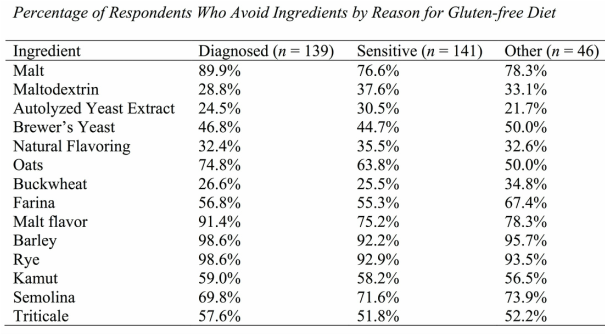

I recently presented my Master's thesis study at the International Celiac Disease Symposium in Prague and am excited to share my results. Note that this study is not yet published in a peer-reviewed journal; please view the results as a call for more research to demonstrate the differences and risks among those following a gluten-free diet in the US. Introduction: Approximately 2.5 million Americans are currently undiagnosed but suffering from celiac disease (CD). The rising number of individuals in the US following a gluten- free diet (GFD) prior to undergoing testing for CD precludes them from obtaining an accurate diagnosis. It is unknown if dietary compliance in these individuals is adequate to avoid the health-related outcomes of untreated CD. The purpose of this study is to determine the degree of GFD compliance in Americans on a GFD but not diagnosed with CD. Results of this study may illuminate health risks for those who have begun a GFD without ruling out a CD diagnosis. Hypothesis: Individuals with a formal diagnosis of CD will have higher dietary compliance scores than those undiagnosed with CD. Study Population: Inclusion Criteria: Adults at least 18 yrs of age, living in the US, English- and computer-literate with internet access, and self-identify as following a GFD, where gluten means “the protein component of wheat, barley and rye” Recruitment: Facebook, Reddit, Celiac Disease Foundation website, Celiac Listserv, word of mouth Methodology: Data collection tool: Self-report online questionnaire (Surveymonkey.com) Interpreting Dietary Adherence Score: Score 0-1 = Non-compliant - positive EMA and/or persistent villous atrophy* Score 2 = Not significantly correlated to EMA or villous atrophy* Score 3-4 = Compliant - negative EMA and/or no villous atrophy* *In Biagi et al (2012) 89.3% respondents’ scores correlated with IgA Endomysial Antibody (EMA) and/or villous atrophy for score categories 0-1 and 3-4; score 2 not significantly correlated with either measure of dietary compliance. Statistical analysis: Chi-square tests for significant differences between groups with bivariate data (p<.05); ANOVA tests with Tukey post-hoc analysis for continuous data (p<.05) Results: A total of 324 individuals who participated in the study met inclusion criteria, and were included in data analysis. 139 self-identified as diagnosed with celiac disease or dermatitis herpetiformis, 141 self-identified as sensitive to gluten, and 46 self-identified as following the diet for some other health-related reason, such as to treat a different disorder. Demographic Differences Between Groups Significantly more women than men were following a GFD for a reason other than a diagnosis of celiac disease (47.3% and 16.9% of women vs. 26.6% and 3.1% of men, for gluten sensitivity and other health reason respectively). The most common reason that men were following a GFD was because of a diagnosis of celiac disease (70.3% of men). Education level was not significantly different based on reason for following a GFD (data not shown). The majority of those following a GFD for five or more years are diagnosed with celiac disease (58.0%). The majority of respondents following a GFD for 6 months to 4 years, however, are sensitive to gluten (51.7%). The majority of respondents following a GFD for less than 6 months (42.3%) reported doing so for other health reasons. Differences in Dietary Adherence Between Groups Individuals diagnosed with celiac disease were found to have significantly higher dietary adherence than those following a GFD because of gluten sensitivity or another health-related reason as defined by the Biagi et al (2012) dietary adherence score (chi2 = 23.89, p = 0.002). The majority of all respondents however (70.2%) were considered highly adherent to a GFD (Biagi score of 3-4). 47.4% of the non-adherent group (score 0-1) cited gluten sensitivity as their reason for following a GFD, 25.0% cited other health reason, and 21.1% cited celiac disease. Dining out Behaviors by Reason for Following GFD Note: superscripts indicate significant difference between groups in Tukey post-hoc analysis There were no differences in frequency of dining out between groups by reason for following the GFD (F = 0.002, p = 0.998). Those diagnosed with celiac disease were significantly more likely than the gluten-sensitivity or other health reason groups to tell their server or cashier that their meal needs to be gluten-free when dining out (F = 10.75, p = 0.000). Those with celiac disease were significantly more likely than those with gluten sensitivity to order from a designated gluten-free menu (F = 4.00, p = 0.019) and to talk to a chef (F = 3.81, p = 0.023); the difference between these groups and the “other health reason” group was not statistically significant. Those with celiac disease and gluten sensitivity were similarly likely to inform a friend or acquaintance about their dietary needs if dining at another person’s house or event, but those with celiac disease were significantly more likely than the other health reason group (F = 7.22, p = 0.001). Other Behaviors by Reasons for Following GFD Note: superscripts indicate significant difference between groups in Tukey post-hoc analysis All three groups were similarly unlikely to eat a food if it did not have an ingredients label (F = 2.12, p = 0.121). Those with celiac disease were significantly less likely to eat a product containing oats that was not labeled gluten-free than both other groups (F = 5.67, p = 0.004). Those with both celiac disease and gluten sensitivity were significantly more likely than the other health reasons group to choose naturally-gluten-free grains labeled gluten-free (F = 3.25, p = 0.040). Those with celiac disease were also significantly more likely to check ingredients of medications, vitamins and supplements for gluten than those following a GFD for other health reasons (F = 4.16, p = 0.016). Those with celiac disease were more likely than the other health reason group to check personal care products for gluten, but this was not statistically significant (F = 2.89, p = 0.057). Statistical significance was not calculated for differences between groups on ingredient avoidance. Results show, however, that those diagnosed celiac disease more often correctly identified ingredients to avoid on a GFD. Discussion:

Strengths This is only the second study to this researcher’s knowledge at the time of this publication to compare dietary adherence behaviors between different subpopulations of the GFD community. The sample sizes of individuals with CD, gluten sensitivity, and other health reasons for following a GFD were large enough to reach statistical significance and illuminates likely differences in dietary compliance between groups following the GFD for the above reasons. The significant differences between groups of individuals following a GFD collected by this study imply that further research should be done to better demonstrate these differences in a larger population. The results of this study are consistent with many of the findings of the other study known to examine GFD compliance behaviors between those with CD and those with non-celiac gluten sensitivity: Verrill, Zhang and Kane (2013). Results of the two studies coincided in that CD and gluten sensitive groups were similar at frequency of reading a food label (94% versus 95%). Verrill et al (2013) found that individuals with gluten sensitivity read labels less often and reported more difficulty with following a GFD. The present study echoes those results; individual with gluten sensitivity were less accurate at identifying gluten-containing ingredients on food labels than those with CD, and also were found to have less dietary compliance than those with CD. The present study further elaborates the findings of Verrill et al (2013) by including a third group of individuals who don’t consider themselves sensitive to gluten but are following the GFD for health-related reasons. It also further elaborates GFD compliance behaviors beyond label-reading and includes dining out behaviors, medications, supplements, and cosmetics, and utilizes a validated tool (Biagi et al 2012) to compare dietary compliance between groups. Several consumer research firms (The NPD Group, Packaged Facts, Institute of Food Technologists) have investigated the GFD trend from a sales perspective to understand why, how often, and how many people are choosing gluten-free foods. This study answers the question “how well”, and is also only the second study in the U.S. known to this author to examine the diet compliance behaviors of GFD followers outside of those with CD. Weaknesses Sampling of individuals was convenience-based and not randomized; this limits its external validity and generalizability to the greater American population following a GFD. The sample was also limited to individuals who were English speaking and computer-literate with access to the online survey by the nature of the research method. The sample surveyed in this study is therefore not representative of all individuals following a GFD in the U.S. This study relied on the Biagi et al (2012) dietary adherence score for comparisons of dietary adherence between groups of respondents, and assumed that this study was not flawed in its methods and analysis. This study also relied on individual self-report as the source of information, which may not accurately reflect the medical diagnosis they received. Using self-report, however, did capture the effect of an individual’s perception of their reason for following a GFD, which may be more important to strict dietary compliance than the actual diagnosis received given that individuals who believed that accidental gluten exposures were important to their health were found in this study to have highest dietary compliance scores. Conclusion: Significant differences exist in the level of compliance to a GFD based on an individual’s reason for following the diet. Efforts need to focus on correctly diagnosing and disseminating accurate information to individuals who have a life-threatening need for following the GFD. Without a diagnosis of celiac disease, individuals are less likely to have accurate information and/or follow behaviors that are recommended for those with celiac disease. Since being diagnosed with celiac disease in 2009 and experiencing small intestinal bacterial overgrowth from 2010 - 2013, the amount of time I spent thinking and talking about my bowel functions skyrocketed. It could be compared to the meteoric rise in gluten-free products on store shelves in the last five years. If there were a graph displaying my comfort level with talking about poop over my lifetime, it would look like this:

It's amazing how healing it is to speak with others about what's troubling you, have someone else express their concern for your troubles, and even more so if they relate to what you're experiencing. Addicts feel freedom talking with other addicts. Cancer survivors find solace with those who have experienced the same trauma. Veterans routinely hang out at Veterans hospitals to feel a part of their community. Why shouldn't there be a community for sharing about poop problems?

While not everyone can say they've survived a horrific accident, I do think that most people can relate to having to run to the bathroom on occasion, feeling grumpy from constipation, or being embarrassed by smelly gas. Probably fewer people can say they've had fecal incontinence - pooped their pants - or have been afraid to leave the house for fear of being far from a bathroom. This community knows the importance of keeping extra plastic bags, wet wipes and a change of underwear in the car glove compartment just for such emergency situations. They also know the isolation felt from others exclaiming "gross!", "ew!", or "not before we eat!", as if there's ever a good time to talk about it. Even more so, gastrointestinal troubles often happen more than once in a day and several days in a row. They can turn a good day to a bad day in a heartbeat. If you can relate with anything I've said here, please consider finding a support group or community of those with a similar condition. Speaking your truth can set you free. And if you haven't told your doctor yet about these problems, please know that EVERY HEALTH PROVIDER TALKS ABOUT POOP. There is no one less embarrassing to speak with about your poop than your doctor, your nurse, or your dietitian. |

AuthorJanelle Smith, Registered Dietitian Nutritionist, specializing in gastrointestinal disorders Archives

August 2016

Categories

All

|

|

Contact: me@JanelleSmithNutrition.com 949-697-7248 Connect on LinkedIn Like and Review on Facebook All rights reserved © Janelle Smith Nutrition |

Janelle Smith, Registered Dietitian Nutritionist |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed